- calendar

- Painting

- Ceramics

- Creative Cafe

- private Groups

- kids & teens

Spring, Summer & Autumn

REGISTRATIONS OPEN NOWSpring, Summer & Autumn

REGISTRATIONS OPEN NOW - gift shop

- memberships

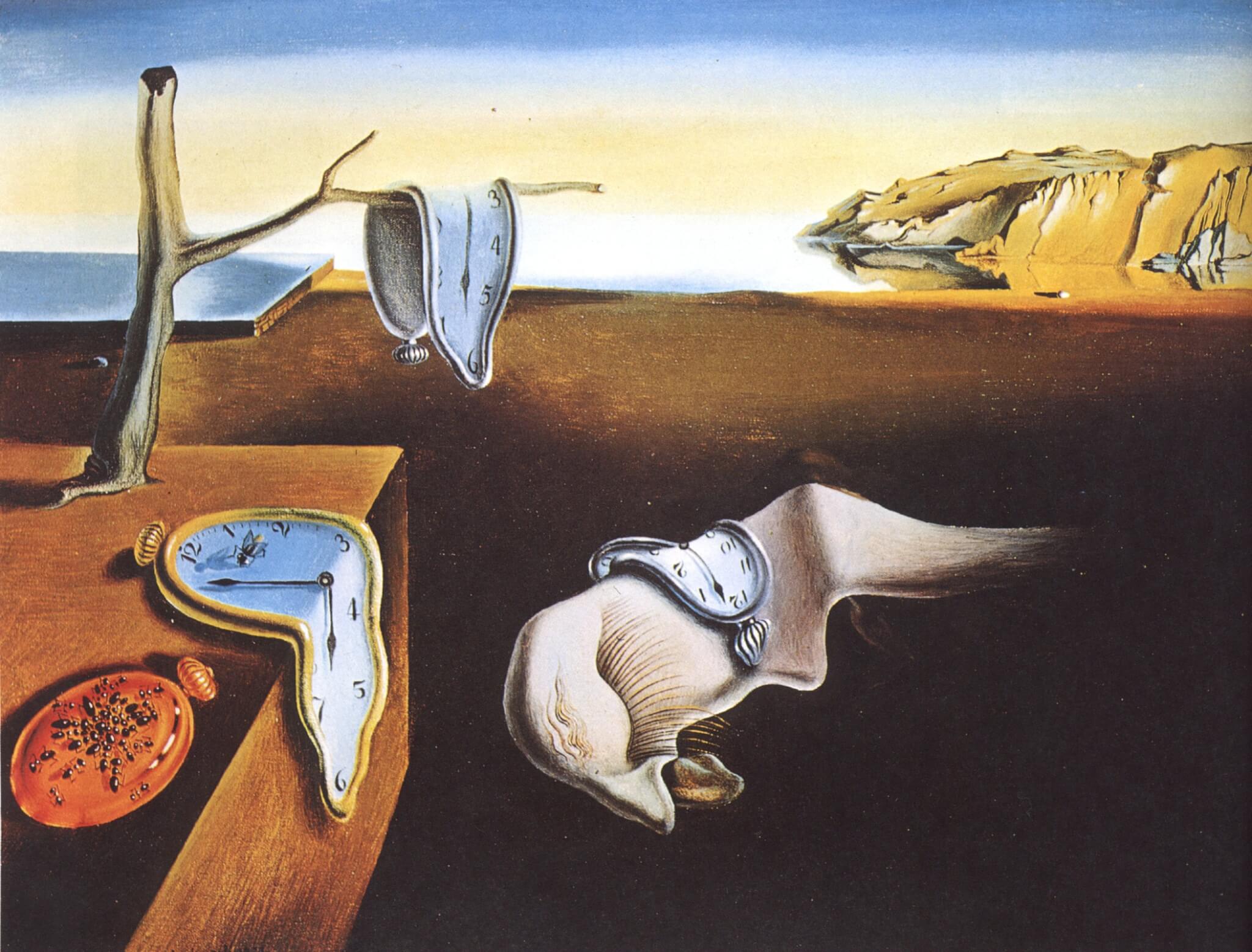

'SALVADOR DALÍ: PERSISTENCE OF MEMORY'

When?

2021 June 05th (Saturday) - 18:00Where?

14. Wallstrasse, 4051 BaselLength of event:

3,5 hoursTell your friends:

65CHF

Dalí painted The Persistence of Memory in 1931 when he was just 28 years old, and the Surrealist movement was at its height. By this time, he was formally involved with the Surrealists and had developed his “paranoiac-critical method” for creating art. Through this method, Dalí would self-induce a hypnotic state that allowed him to break free of reality. It was his hope that once he was unfettered, the visions for his paintings might begin. The Persistence of Memory is a physically small work for the large art-historical and pop-cultural reputation it holds—the painting is just a couple of inches wider than a standard piece of computer paper. The piece may seem rooted firmly in an imaginary world, but the cliffs in the background have been identified as the coast of Catalonia, Dalí’s hometown. Though the cliffs bring an element of reality to the ambiguous scene, distorted clocks melt on a dead tree, an inexplicable platform, and a flesh-colored amorphous form (identified as a self-portrait of the artist in profile). Ants swarm to a closed timepiece as if it were flesh, and the landscape gives the impression of total, eerie stillness. Dalí proclaimed that he didn’t know the meaning of the work—this has given scholars and art lovers alike plenty of room to impose meaning on the painting. While the clocks are widely thought to symbolize the omnipresence of time, Dalí refused to associate them with anything other than a French cheese: He referred to them as the “camembert of time.” Dalí takes hard, mechanical objects and renders them limp—although time controls society’s waking hours, it is often bent in dreams and in memory. The gathered ants (and the single fly, perched on a clock) appear as they might on rotting flesh, alluding to death and decay. These objects are familiar, but distorted and taken out of context, as things often are in dreams. The face-like form, sleeping in the center of the work, looks like a bone-dry cow skull at first glance. With time, the skull begins to reveal human characteristics: long eyelashes, a nose, and even the wisp of a curled mustache. This isn’t the last time Dalí would include many of these symbols in his work, and around 30 years later, he returned to The Persistence of Memory with The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory (1952–54). The work takes his 1931 painting and updates it to reflect the more contemporary anxiety of nuclear warfare. Dalí referred to work from the early 1950s as part of his “Rhinocerotic period”—rhinoceros horns that evoke missiles launched under water.